As the United States and China reconsider their geopolitical priorities in a world heading towards a multi-polar confrontation, the economic relationship and cooperation between China and the Gulf states are likely to increase competition and tension between these two rivals.

Just one month after the Arab-China Summit held on December 9th at the King Abdelaziz International Conference Center in Riyadh, the finance minister, Mohammed al-Jadaan, stated in an interview with Bloomberg in Davos, Switzerland, “There are no issues with discussing how we settle our trade arrangements, whether it is in the U.S. dollar, whether it is the euro, whether it is the Saudi riyal,” (1) Ali Shihabi, a member of the Advisory Board of Neom, also commented on the importance of China’s relationship with Saudi Arabia in a series of tweets, stating that “China is Saudi Arabia’s largest customer for oil and an increasingly important military and political ally. Its desire to pay for oil imports in its own currency is not something the Kingdom can ignore.” He also stated, “Freezing Russia’s foreign exchange reserves must have scared the daylights out of the Chinese (and others) who hold massive reserves in dollars. Any doubts countries had about the need to diversify into Yuan and other currencies/geographies would have ended with that huge step.” (2)

These statements have led to speculation about Riyadh’s intention to trade oil sales in Chinese yuan and serve as a reminder of the Petro-dollar system, which cemented the dominance of the U.S. dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency in the 1970s. The story of the U.S.-Saudi relationship dates back to 1974 when the two nations made a secret agreement. The United States promised to offer military protection to Saudi Arabia, and in return, the Saudis agreed to price their oil in dollars. This agreement played a vital role in establishing the U.S. dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency. As a result, countries worldwide were compelled to hold significant reserves of dollars to buy oil. (3)

Saudi Arabia’s attempt to explore new trade arrangements is not isolated. Over the years, tensions between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia have been escalating, and the UAE has also expressed frustration with the diminishing role of the U.S. in the region. The decline in confidence in the U.S. commitment to regional security has coincided with a historic upgrade in relationships with China after the first Arab-China summit. Although the U.S. relationship with other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members, mainly Qatar and Kuwait, has not yet reached the same level of tension, there is a growing sentiment that the Gulf region is no longer a priority for U.S. policymakers. Additionally, the U.S. attitude towards different crises like Iran’s activities, the Qatar blockade, the war in Yemen, and other security challenges have prompted doubts about the future of the US-GCC relationship.

Since the Iraq War in 1991, the United States has maintained a strong military presence in the Gulf and has been a key ally of the GCC countries, particularly in terms of security and defense. However, over the years, the U.S.-GCC relationship has had its ups and downs, passing through several shocks from 9/11 to the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, but it has never reached this level of distrust.

The list of areas of disagreement with the U.S. is growing, topped by the perceived threat from Iran. Despite the U.S.’s pursuit of a policy of maximum pressure on Iran, including economic sanctions, that effort has been insufficient from the Saudi-UAE-Bahrani perspective to keep Iran’s behavior in check. These countries accuse the U.S. of being too lenient with Iran. Another example of the strain in the U.S.-GCC relationship is the Russian war, which served as a catalyst for some GCC members to express their frustration publicly by avoiding condemning the Russian invasion and refusing to decrease oil production during OPEC+ meetings. (4)

As challenges continue to mount, both domestically and internationally, GCC countries are re-evaluating the usefulness of their security agreement with the U.S. This agreement was primarily transactional in nature and was prompted by security concerns. The emergence of a new multipolar reality has also played a role in this re-examination. China has taken note of this shift and has been quick to capitalize on it. It has tripled its economic cooperation and bilateral trade with the GCC countries, while also expanding its influence in the military sphere. China’s actions have been so significant that they can no longer be ignored by Washington. (5)

Although it would be a mistake to view the Chinese-Gulf relationship solely through the lens of rivalry, the erosion of the global order and the birth of a new one, headlined by the idea of the Petro-yuan system, seems intriguing and sends a strong message. While the concept of a Petro-yuan system is ambitious, many challenges and uncertainties would need to be overcome before it becomes a reality. However, the fact that the idea has been discussed indicates mounting pressure on GCC countries to navigate different options, including looking east to drive their economic transformation and meet their security needs. In other words, striking a new security interest-driven agreement with Beijing has become a strategic decision for the GCC states, rather than just a desire to share an economic relationship. (6)(7) Nonetheless, building a solid relationship with China could have drawbacks, particularly regarding the United States. Within this framework, the million-dollar question is: How far are the GCC countries, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE, willing to go with their cooperation with China, and what red lines are tolerated by Washington?

Realism of the Petro-Yuan System in the FutureThe concept of a “Petro-yuan” system, where oil is priced and traded using the Chinese Yuan instead of the U.S. dollar, has been under discussion for several years. Its objective is to diminish the dollar’s dominance in the global oil market and provide China with a more significant influence in the global economy. President Xi has called for China and Gulf nations to utilize the Shanghai Petroleum and National Gas Exchange as a platform to carry out yuan settlements of oil and gas transactions. (8) However, the establishment of a Petro-yuan system is a complex and uncertain prospect for several reasons. Firstly, the U.S. dollar has been the dominant currency in the global oil market for decades, and changing this established system would likely face significant resistance. Secondly, many oil-producing countries have strong economic ties to the U.S. and may be reluctant to move away from the dollar.

Another essential factor to consider is the Chinese economy itself. Despite China’s significant economic growth over the past few decades, it still faces many challenges, and its status as a global superpower is still developing. In particular, China’s economic model has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and its economy is still facing worrisome symptoms. Therefore, it’s unclear whether China can sustain its growth rate over the following decades (9). Furthermore, the Yuan’s main problems are its volatile liquidity and short-scale extension due to the tight controls that Beijing keeps on it. These factors could hinder the development and implementation of a Petro-yuan system, as they may undermine confidence in the currency’s stability and reliability as a trading medium.

However, as China continues to grow and develop, it may be able to address these issues and become a more viable alternative to the U.S. dollar in the global oil market. In recent years, the Chinese government has been trying to solve this key challenge by increasing its gold reserves to back the yuan, stabilizing it and making it more attractive to investors outside of China. In addition, China has been making efforts to promote the use of the Yuan in international trade and finance and has also been increasing its investments in the oil and gas sector. Thus, if the yuan is gold-backed by the Chinese government, it will strengthen its position as a safe currency and reassure its trading partners who are hesitant to use it instead of the dollar. These efforts could lay the foundation for a Petro-yuan system in the future, but it is difficult to predict how successful these efforts will be. (10)

Moreover, the increasing weaponization of the dollar makes using the Petro-yuan system an indispensable alternative. This would enable countries to bypass the need to hold U.S. dollars for oil transactions, reducing demand for the dollar and potentially weakening its status as the dominant global reserve currency. In other words, pushing the dollar from its throne will give countries like Russia and Iran the option to avoid U.S. sanctions, while also providing other countries such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE a way to prevent future U.S. pressure. (11)

In summary, China’s efforts to establish the Petro-yuan system represent a significant step towards challenging the existing financial order and could pave the way for a more multipolar global economic system in the future. However, the question is whether the Yuan can succeed where the Euro failed to dethrone the dollar. The answer, at least in the foreseeable future, is ‘no’ due to the many challenges and uncertainties that need to be overcome before it becomes a reality. The dollar’s leading position will likely remain unchallenged in the global oil market for years to come. Nevertheless, the fact that Saudi Arabia is considering ditching the dollar shows that the dollar’s position as the only dominant currency is unfavorable. If the right conditions are met, the concept of the Petro-yuan system may undermine the dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency in the future. While the success of the Petro-yuan system is far from certain, it has the potential to disrupt the global financial status quo and usher in a new era of economic power dynamics. (12)

China’s evolving economic cooperation with the GCC states

China’s bilateral trade with GCC countries has undergone significant changes in recent years. As the two sides look to deepen their economic ties, bilateral trade exceeded $157 billion in 2021 and is expected to move into a new phase following the first Sino-Arab summit. During the summit, the Chinese president mentioned five major areas for cooperation between China and the GCC countries: energy, finance and investment, innovation and new technologies, aerospace, and language and culture. (13)

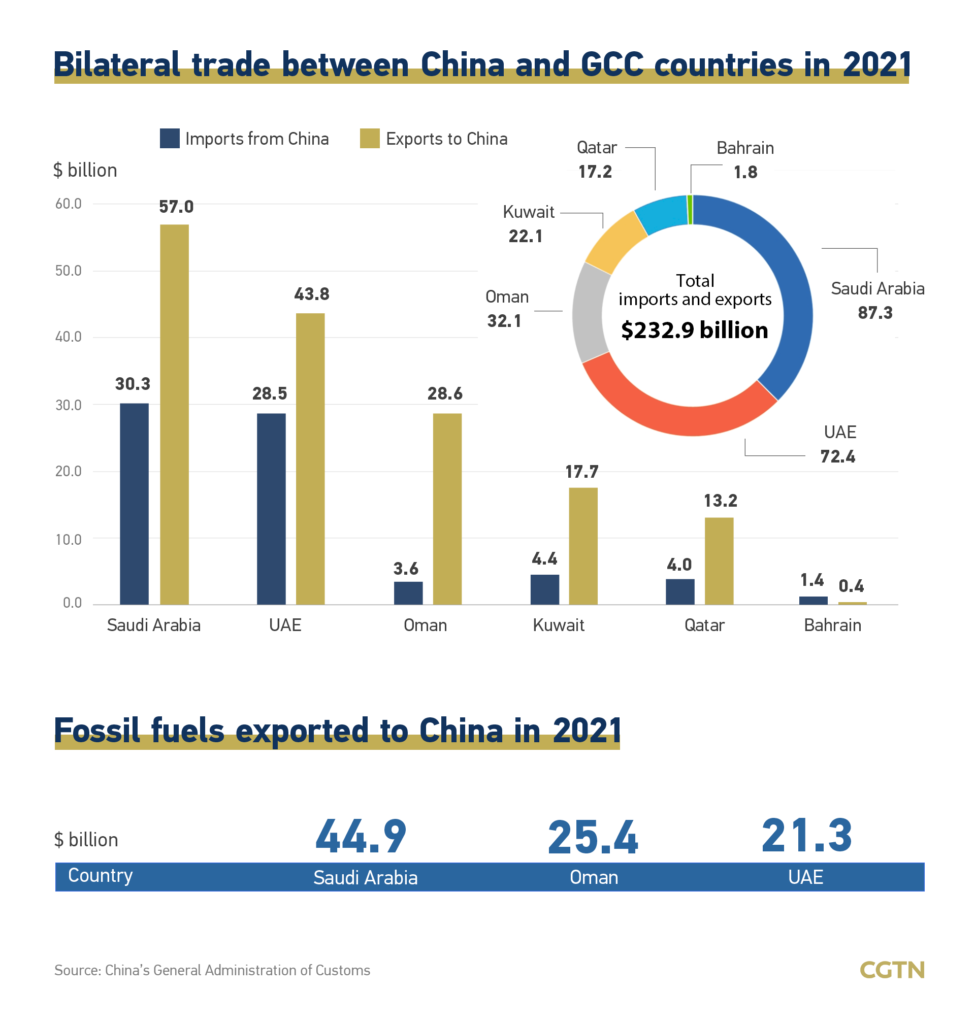

China’s huge demand for and growing dependence on oil and gas imports are making it increasingly reliant on GCC countries as a critical source of energy. In response to this demand, China’s crude oil imports from Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the UAE exceeded $44.9 billion, $25.4 billion, and $21.3 billion, respectively. Furthermore, the total Chinese investment in the Middle East and North Africa region has reached $213.9 billion, with Saudi Arabia being the biggest beneficiary of Chinese investments, having received $43.47 billion between 2005 and 2021. (14)

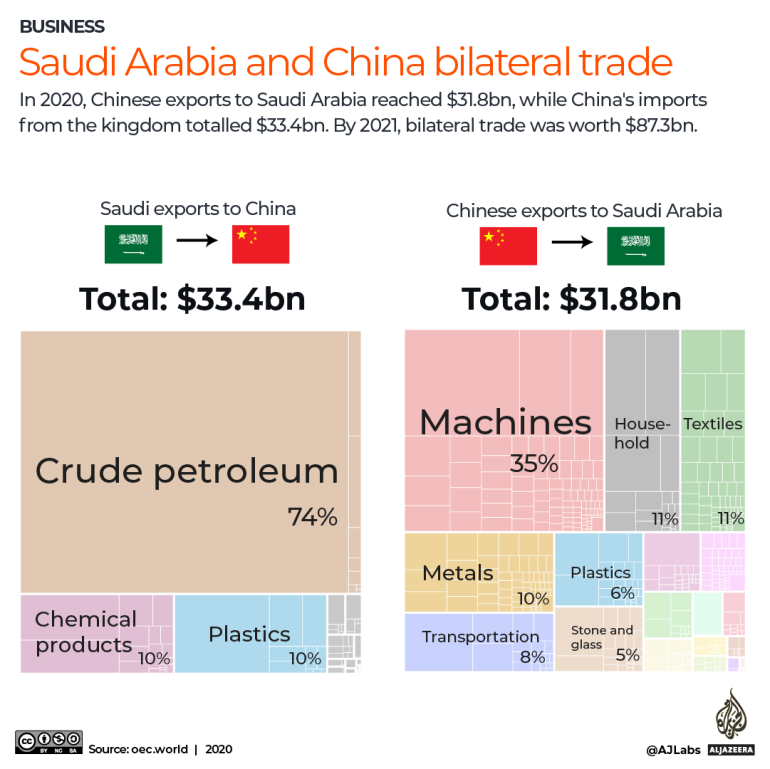

Figure 1: Figure 1: Saudi Arabia and China Saudi Arabia and China BBilateral bilateral TradeTrade(15)

More importantly, in recent years, China has strived to bolster its energy security by investing heavily in the GCC’s energy sector through direct investment in oil and gas projects and strategic partnerships with local companies. In 2022, China’s state-owned company Sinopec signed one of the largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) deals ever with Qatar, with a more than $60 billion agreement for purchases of LNG over the next 27 years, starting in 2026. (16) In the same vein, Saudi Arabia maintained its ranking as a top supplier of crude oil to China in 2021, totaling 17% of Chinese imports, with an increase of 3.1% compared to 2020. However, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) ranked second among GCC countries in crude oil imports to China, just after Saudi Arabia. (17)

Figure 3: Fossil Fuels Exported to China (18)

Furthermore, Beijing expanded its trade with GCC countries from $89.59 billion in 2010 to $157.38 billion in terms of trade exchange in 2021. With these numbers, China has become the GCC countries’ largest trading partner, replacing the European Union.

Saudi Arabia ranked first among China’s trade partners in the Gulf region with a total of $87.3 billion in trade exchange in 2021, followed by the UAE with $72.4 billion. China also topped the list of trade exchanges with Oman, reaching $32.1 billion in 2021. The trade exchange between Kuwait and China amounted to $22.1 billion in the same year. Although Qatar’s exports of LNG to China increased, the trade exchange nearly tripled from $4.55 billion in 2010 to $17.2 billion in 2021. On the other hand, the volume of trade exchange between Bahrain and China decreased from $2.26 billion in 2019 to $1.8 billion in 2021. (19)

Based on these numbers, China’s economic cooperation with the GCC states has evolved significantly in recent years, reflecting the changing dynamics of the global economy and China’s growing role as a major economic power. While there have been both opportunities and challenges to this cooperation, it is clear that China will continue to play an important role in the region in the years to come.

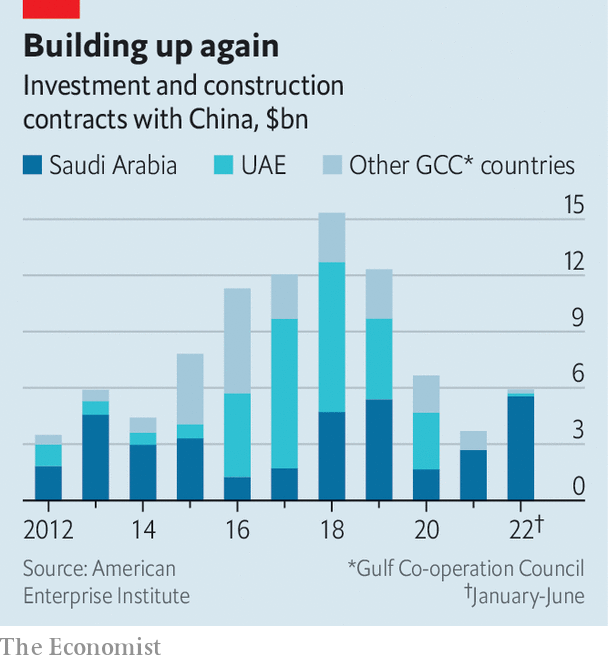

Figure 4: The Chinese Investment and construction contracts with GCC countries (20)

How much do the GCC states trust the U.S. as a security provider in the region?

The extent to which the GCC states trust the U.S. as a security provider in the region is still debatable due to several factors. One of the main reasons is the changing dynamics in the region, including the rise of actors such as Iran and its proxies. This shift in the balance of power has led many Gulf countries to view the U.S. as less able or less willing to provide the level of security they previously relied on. Additionally, the U.S. has been increasingly focused on other global priorities, such as the ongoing conflict with Russia, which has reduced the number of U.S. troops and resources in the region. This has caused many Gulf countries to see the U.S. as less committed to the region’s security. (21)

It is worth mentioning that not all members of the GCC hold the same perspective on the security benefits provided by the United States. However, with a clear understanding of what China may offer in the future, a rational view consistently favors the U.S. as their primary and indispensable security guarantor. (22) While Saudi Arabia and the UAE may be inclined to diversify their partnerships and form new alliances with China to address security challenges and advance their interests, the other GCC members prefer to maintain strong ties with China while still upholding their security alliance with the U.S. As a result, all members find themselves caught in a difficult position between the economic advantages offered by China and the security and military presence provided by the U.S., making neutrality an unrealistic option. This illustrates their vulnerability to the intricate power dynamics between the two rivals. (23)

Furthermore, as the rivalry with Iran has grown over the years and taken on a more aggressive tone, the U.S. disengagement and hesitancy towards Iran’s nuclear program and its activities in the region have only increased. This situation has compounded the rift between the U.S., Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, affecting the long-standing view of the U.S.’s role in the region. The rift intensified even further when the Biden administration made a clean break after Biden’s inflammatory comments about Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. As a result, the U.S. reduced its assistance of intelligence support for the Saudi-UAE war effort in Yemen. The latter drew much criticism from lawmakers and activists urging the Biden administration to take a more assertive stance towards the war in Yemen, including suggesting sanctions or taking other measures to hold them accountable for their actions during the war. The U.S.-UAE diplomatic relationship has also experienced apathy, with Emirati President Muhammad Bin Zayed refusing to meet with CENTCOM Commander General McKenzie and rejecting a call from President Biden to increase oil production to reduce oil prices. (24)

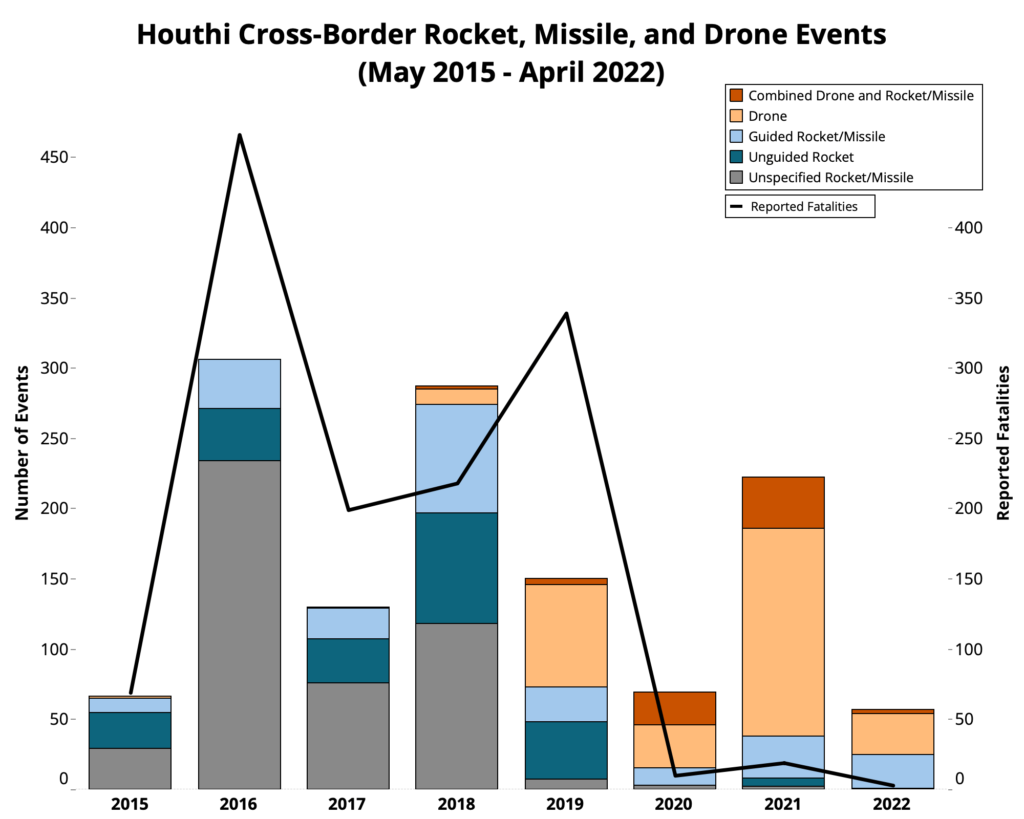

The failure of the U.S. to prevent the Houthis from launching attacks in the region is a significant test of its commitment to the region. Unfortunately, this failure has exposed the limitations of U.S. power, as the Houthis have been able to launch attacks on Saudi Arabia and the UAE with little consequence. According to many reports, the Houthis have carried out over 400 cross-border air attacks using rockets, missiles, and drones between May 2015 and 2022. (25)

Figure 5: Beyond Riyadh: Houthi Cross-Border Aerial Warfare 2015-2022 (24)

This has created a deep-rooted security gap in the region that remains unfilled. As a result of this situation, Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have adopted a more proactive approach to their security. They have sought closer military ties with China as they no longer view the United States as a reliable partner in the region. (26)

Another argument that strengthens the view that Washington has left a security gap in the Gulf region is the failure to further enhance their security and military ties, even after decades of cooperation. Bilal Y. Saab, a Senior Fellow at the Middle East and U.S. policy, has expressed in his research paper titled “Integrated Deterrence with the Gulf” that the Gulf states have not enjoyed the same level of security cooperation as NATO countries due to the lack of democratic values. However, he argues that this is not the only or most important reason why considerable gaps in security relations have persisted for so long. In his view, what is needed more than anything else in U.S.-Gulf security ties is a coherent structure that includes norms, mechanisms, and procedures for strategic consultation and coordination. This would enable the United States to work more closely with Gulf states in addressing security concerns in the region. (27)

However, the change in American administrations often results in changes in policies and priorities, making it challenging to create a coherent structure that leads to enhanced security cooperation while avoiding future deterioration in relations. These factors have further nurtured the idea of a security gap in the Gulf and eroded the perception of the United States as a reliable security guarantor in the region. Therefore, it is critical to establish a framework for more effective security and military cooperation, regardless of the changes in administrations, to prevent security gaps and ensure the safety of the region. (28)

Could Chinese-GCC Economic Ties Evolve into a Strategic Alliance?

To assess the likelihood of a future strategic alliance between China and the GCC based on their current geo-economic relationship, it is important to examine China’s policies in advancing its interests in comparison to those of the U.S. First, it is worth noting that China’s approach to achieving dominance and building a strategic alliance with the GCC would differ significantly from that of the U.S. For instance, the U.S. built its strategic alliance through a military intervention aimed at protecting its allies in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. In contrast, China relies mainly on its economic power and adopts a non-interventionist stance in the region to drive its geopolitical approach. Additionally, China has been forging smooth diplomatic and economic ties with GCC members collectively as a whole, while simultaneously strengthening its security and military collaboration with each GCC member individually, rather than relying on a collective security umbrella in the region. (29)

Moreover, Beijing has always employed a different approach to exert its influence, using unconditional economic, military, and diplomatic cooperation while promoting the idea of “shared interests.” In contrast, the U.S. has a long history of using economic and diplomatic pressure to influence other countries’ foreign policies, attaching conditions related to human rights to maintain an exclusively economic and military alliance. This approach often ends with economic sanctions, a reduction in military cooperation, or even a deterioration of diplomatic relations. While it is possible for the Chinese-GCC relationship to evolve into a strategic alliance in the future, several factors need to be considered.

One crucial factor in the potential elevation of the Chinese-GCC relationship to a strategic alliance is the development of the political and security environment in the region. Recently, tensions with Washington have led Saudi Arabia to seek help from Beijing to improve its missile capabilities, and reports suggest that China is building a secret port facility for military purposes in the UAE. (30) Similarly, China has convinced three Gulf nations, the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, to partner with Huawei to build their 5G network, despite Washington’s warnings about the security risks posed by the Chinese tech giant. (31) All of these developments suggest that some GCC members may be seeking to form a closer alliance with China, hoping that this new player in the Gulf arena will offer a strategic alliance with similar benefits to what the U.S. has provided thus far.

Another critical factor is the evolution of the Chinese-GCC relationship after Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia for the Chinese-Arab summit, where Saudi Arabia agreed to upgrade its bilateral relations with China to a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership,” following the UAE. The magnitude of the deals signed during the summit and the fanfare that followed suggest that the trip successfully tested the Gulf countries’ inclination to pursue independent calculations of their interests while giving China a foothold in a region crowded with military alliances. Although the comprehensive strategic partnerships with GCC countries are still a work in progress, China is clearly determined to build a regional security alliance with GCC states. (32)

Thus, if economic ties between China and GCC countries continue to grow and diversify, it could lead to increased cooperation in other areas, such as defense and security, potentially resulting in a strategic alliance. Jonathan Panikoff, the director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Program, stated that “many global relationships and alliances, bilaterally and multilaterally, began this way and then expanded to other realms, including in the traditional defense areas”. (33)

However, it is important to note that several factors could impede the formation of a strategic alliance. First, the U.S. holds significant negotiating power and capacity to shape and impose its agenda. Second, by providing concessions to Gulf countries, mainly Saudi Arabia and UAE, the U.S. could prevent them from shifting alliances while strengthening their sense of continuity. Third, the U.S. could rebalance and recalibrate its long-standing security engagement to avoid further damage to its relations with allies.

Furthermore, Beijing doesn’t separate its military and civil efforts when building an alliance with other countries. Its economic initiatives are cooperative in nature, yet they are strategic in origin and designed to compete with the U.S. to meet Beijing’s needs to exert influence worldwide. (34) Therefore, some GCC countries may have varying levels of enthusiasm for being a source of any future heated rivalry and may reject the idea of choosing Beijing as a partner of choice against the U.S.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the GCC countries have become increasingly aware of the declining power of the U.S. and the growing influence of China on the global stage. This awareness was heightened after the attacks by the Houthis, which resulted in a growing security gap between the U.S. and its regional allies. Additionally, the US’s plans to reduce its military presence in the Gulf without losing influence in the region have backfired, eroding regional confidence in the US’s reliability. (35)

Thus, if the situation persists, it could determine the GCC’s next move toward China to address their pressing security challenges in the future. However, as the competition between China and the U.S. intensifies and economic decoupling takes place, they will find themselves facing a rigid dichotomy: choose economic prosperity or protect national security.

Overall, whether GCC countries will choose China as a security guarantor or maintain their strategic alliance with the U.S. in the region remains an open question that has yet to be answered. This will depend on how far Saudi Arabia and the UAE are willing to go to be more independent from the U.S. and how close they are ready to move toward Beijing.

For now, while there may be concerns about China’s growing influence in the Gulf, the U.S. is unlikely to take any drastic measures to curtail this relationship unless it undermines its interests. The key point here is that the U.S. will ensure that the economic dimensions of the Chinese-GCC partnership do not evolve into a security alliance of strategic significance. Conversely, if China’s influence continues to expand in the region, Beijing will eventually gain significant leverage over the GCC states. This raises questions about how the U.S. will respond to this growing partnership. More importantly, China will have to make difficult decisions to elevate its economic relationship into a security alliance in the Gulf region. Beijing still needs time to fully prepare to take on the role of a security guarantor in the Gulf, including filling the US’ shoes in the region. The most challenging aspect of deepening strategic ties with the GCC is managing its relationship with Iran. While it is still being determined whether China will prioritize its relationship with the Gulf countries over Iran, the GCC countries appear to be more reliable partners than sanctioned Iran. (36) Thus, a shift in Beijing’s strategy toward the Gulf region will be a prerequisite for any successful security alliance in the future.

The GCC countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, currently do not have the option of replacing their U.S. security alliance with one with Beijing. However, looking East will always be an open option for them, driven by the new opportunities that China could offer to diversify their alliances and reduce their dependence on the U.S. But how far they are willing to go despite the consequences they may face if they cross Washington’s red lines will depend on the circumstances. Part of their future calculation to elevate their relationship with China will depend on whether they can count on the U.S.’s willingness to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons.

Looking ahead, the GCC countries will find themselves in an unprecedented position to ensure their security. As a result, they will likely continue to test Washington’s red lines by pushing their relationship with China to pressure the U.S. to meet its security commitments. However, both the U.S. and China will eventually expect the GCC countries to take sides. On one hand, the U.S. will appeal to Gulf countries to help isolate China, while on the other hand, China will use its economic leverage to undermine the U.S.’s role as a security provider.

Most strategically, the GCC countries will have to balance Beijing’s economic leverage and Washington’s red lines, in other words, resist the option to choose between their economic and security interests. Whatever decision they make will undoubtedly shape the world order the same way it did during the Cold War.

REFERENCES

(1) MEE staff, “Saudi Arabia open to trading in currencies besides the US dollar”, 26 October 2022, Middle East Eye, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-arabia-open-trading-currencies-besides-us-dollar

(2) Ali Shihabi, Mar 15, 2022, Twitter, https://twitter.com/aliShihabi/status/1503732428552220678

(3) “The untold story behind Saudi Arabia’s 41-year US debt secret”, Jun 01,2016, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/business/the-untold-story-behind-saudi-arabias-41-year-us-debt-secret/articleshow/52528470.cms?from=mdr

(4) Dr Sanam Vakil, “Biden’s Middle East trip shows the long game is his aim”, JULY19, 2022, Chatham House, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/07/bidens-middle-east-trip-shows-long-game-his-aim

(5) Gerald M. Feierstein, Bilal Y. Saab, Karen E. Young, “US-GULF Relations At The Crossroads: Time For A Recalibration”, APRIL 2022, The Middle East Institute, www.mei.edu/sites/default/files/2022-04/US-Gulf%20Relations%20at%20a%20Crossroads%20-%20Time%20for%20a%20Recalibration.pdf

(6) Rachna Uppal, Gulf states, “looking East, to reinforce economic ties with China as Xi visits Saudi,” Reuters, December 6, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/gulf-states-looking-east-reinforce-economic-ties-with-china-xi-visits-saudi-2022-12-06/

(7) Ryan Hass, Patricia M. Kim, and Jeffrey A. Bader, “A course correction in America’s China policy”, November 2022, Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/research/a-course-correction-in-americas-china-policy/

(8) “China to use Shanghai exchange for yuan energy deals with Gulf nations – Xi”, December 9, 2022, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/chinas-xi-tells-gulf-nations-use-shanghai-exchange-yuan-energy-deals-2022-12-09/

(9) Eric Levitz, “China’s Economic Model Is in Crisis”, JAN 24, 2023, Intelligencer https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2023/01/china-economy-property-bubble-reopening-zero-covid.html

(10) FXCM Research Team, “What Is The Petroyuan?”, 24 April 2018, https://www.fxcm.com/uk/insights/what-is-the-petroyuan/

(11) Ebrahim Fallahi, “Petrodollar Vs. Petroyuan, “ is China set to overthrow U.S. in oil market?”, December 10, 2022, Tehran Times, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/479562/Petrodollar-Vs-Petroyuan-is-China-set-to-overthrow-U-S-in

(12) Dmitry Zhdannikov, Rania El Gamal, Alex Lawler, “Exclusive: Saudi Arabia threatens to ditch dollar oil trades to stop ‘NOPEC’ – sources”, APRIL 4, 2019, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-usa-oil-exclusive-idUSKCN1RH008

(13) “China-GCC relations elevated to new level as first China-GCC Summit held in Riyadh”, 09-Dec-2022, CGTN, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-12-09/Xi-Jinping-says-China-GCC-states-natural-partners-for-cooperation-1fCZREQ2L1m/index.html

(14) Syed Raiyan Amir, “China-GCC Summit: Bringing “Strategicness” Into the Domain of Cooperation?”, December 16, 2022, The geopolitics, https://thegeopolitics.com/china-gcc-summit-bringing-strategicness-into-the-domain-of-cooperation/

(15) Al-Makahleh and Giorgio Cafiero, “As US watches on, China-Saudi relations grow in importance, Shehab “, Dec 08, 2022, Al Jazeera Media Network https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/8/analysis-president-xi-jinping-comes-to-riyadh

(16) Walid Ahmed, “China Seals One of the Biggest LNG Deals Ever With Qatar”, November 21, 2022, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-21/china-s-sinopec-signs-long-term-lng-supply-deal-with-qatar?leadSource=uverify%20wall

(17) Saudi Arabia is top oil supplier to China in 2021″, 20 January 2022 20 January 2022, Arab News, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2008206/business-economy

(18) “Chart of the Day: China and the GCC to enhance comprehensive ties”, December 09, 2022, CGT, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-12-09/Chart-of-the-Day-China-and-the-GCC-to-enhance-comprehensive-ties-1fCwZqzVNV6/index.html

(19) “China and the Gulf countries.. Trade exchanges”, December08, 2022, Ashrq Bloomberg, https://now.asharq.com/category/154/%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%89-

(20) “The Gulf looks to China”, Dec 07, 2022, the Economist, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2022/12/07/the-gulf-looks-to-china

(21) Christopher Michele and Prof. Joshua Goodman, “Three Broken Teacups: The Crisis of U.S.-UAE relations”, June 27, 2022, Air University, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Wild-Blue-Yonder/Articles/Article-Display/Article/3071639/three-broken-teacups-the-crisis-of-us-uae-relations/

(22) EMILE HOKAYEM, “Reassuring Gulf Partners While Recalibrating U.S. Security Policy”, May 18, 2021, The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/18/reassuring-gulf-partners-while-recalibrating-u.s.-security-policy-pub-84522

(23) Eugene Chausovsky, “The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Accelerating a Multi-Polar World”, 21 April 2022, Al Jazeera center for studies htps://studies.aljazeera.net/en/analyses/russia-ukraine-conflict-accelerating-multi-polar-world

(24) Christopher Michele and Prof. Joshua Goodman, “Three Broken Teacups: The Crisis of U.S.-UAE relations”, June 27, 2022, Air University, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Wild-Blue-Yonder/Articles/Article-Display/Article/3071639/three-broken-teacups-the-crisis-of-us-uae-relations/

(25) Luca Nevola, “Beyond Riyadh: Houthi Cross-Border Aerial Warfare”, 17 January 2023, ACLED, https://acleddata.com/2023/01/17/beyond-riyadh-houthi-cross-border-aerial-warfare-2015-2022/

(26) Alex Ward, “The US may still be helping Saudi Arabia in the Yemen war after all”, Apr 27, 2021, Vox, https://www.vox.com/2021/4/27/22403579/biden-saudi-yemen-war-pentagon

(27) Gerald M. Feierstein, Bilal Y. Saab, Karen E. Young, “US-GULF Relations At The Crossroads: Time For A Recalibration”, APRIL 2022, The Middle East Institute, www.mei.edu/sites/default/files/2022-04/US-Gulf%20Relations%20at%20a%20Crossroads%20-%20Time%20for%20a%20Recalibration.pdf

(28) Brennen Sharp-Polos, “Blockade on US Interests: Why Washington Must End the Gulf Crisis”, December 19, 2019, The Globe Post, https://theglobepost.com/2019/12/19/qatar-blockade-us-interests/

(29) Nurettin Akcay, “Beyond Oil, A New Phase In China-Middle East Engagement”, January 25,2023, The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2023/01/beyond-oil-a-new-phase-in-china-middle-east-engagement/

(30) Camille Lons, Jonathan Fulton, Degang Sun, Naser Al-Tamimi, “China’s great game in the Middle East”, 21 October 2019, European Council on Foreign Relations https://ecfr.eu/publication/china_great_game_middle_east/

(31) Mohammed Soliman, “The Gulf has a 5G conundrum and Open RAN is the key to its tech sovereignty”, January 12, 2022, Middle East Institute, https://www.mei.edu/publications/gulf-has-5g-conundrum-and-open-ran-key-its-tech-sovereignty

(32) ABDULLAH BAABOOD, “Mr. Xi Goes to Riyadh”, December 21, 2022, The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/88685

(33) Al-Makahleh and Giorgio Cafiero, “As US watches on, China-Saudi relations grow in importance, Shehab “, Dec 08, 2022, Al Jazeera Media Network https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/8/analysis-president-xi-jinping-comes-to-riyadh

(34) Anthony H. Cordesman, “China, Asia, and the Changing Strategic Importance of the Gulf and MENA Region”, October 15, 2021, Center for Strategic & International Studies, https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-asia-and-changing-strategic-importance-gulf-and-mena-region

(35) Ryan Hass, “The “new normal” in US-China relations: Hardening competition and deep interdependence”, August 12, 2021, Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/08/12/the-new-normal-in-us-china-relations-hardening-competition-and-deep-interdependence/

(36) VALI GOLMOHAMMADI, “China’s shifting Persian Gulf Policy: Is it favouring the GCC over Iran?”, January 04, 2023, Observer Research Foundation, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/chinas-shifting-persian-gulf-policy/

Well done!!, keep going forward Mr. Bendaoudi